Access to safe water and sanitation

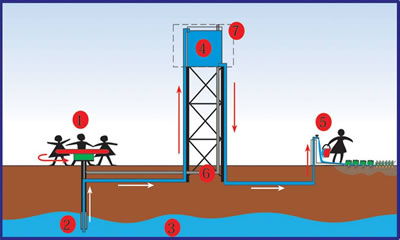

Some 62 per cent of Africans had access to an improved water supply in 2000. Even so, rural Africans spend much time searching for water and 28 per cent of the global population without access to improved water supplies live in Africa. Women are particularly affected as they are often responsible for the family’s water needs. Urban areas are better supplied, with 85 per cent of the population having access to improved water supplies. In rural areas, the average is 47 per cent, with 99 per cent of the rural population in Eritrea having no sanitation coverage. The total African population with access to improved sanitation was 60 per cent in 2000. Again, urban populations fared better, with an average 84 per cent having improved sanitation compared to an average 45 per cent in rural areas (WHO and UNICEF 2000).

Poor water supply and sanitation lead to high rates of water-related diseases such as ascariasis, cholera, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, dysentery, eye infections, hookworm, scabies, schistosomiasis and trachoma.

About 3 million people in Africa die annually as a result of water-related diseases (Lake and Souré 1997). In 1998, 72 per cent of all reported cholera cases in the world were in Africa.

Poor water supply and sanitation lead to contamination of surface and groundwater, with subsequent effects on plant, animal and human communities. The economic costs can be high. In Malawi, for example, the total cost associated with water degradation was estimated at US$2.1 million in 1994 (DREA Malawi 1994). These costs included the need for water treatment, the development of human resources and reduced labour productivity. Meeting basic water and sanitation needs is also expensive. In Nigeria, a recent study estimates the future cost of water supply and environmental sanitation to be US$9.12 billion during 2001-10 (Adedipe, Braid and Iliyas 2000).

Governments are trying to improve the situation with environmental management policies that include waste management and urban planning, and by making environmental impact assessments compulsory for large projects. One of the major regional policy initiatives was the 1980 Lagos Plan of Action, which urged member states to formulate master plans in the sectors of water supply and agriculture (OAU 1980). The Plan was influenced by the 1977 United Nations Water Conference’s Mar del Plata Action Plan and the 1978 African regional meeting on water-related issues. Despite these initiatives, a lack of human and financial resources, and equipment for implementation and enforcement, still limit progress.

Sludge disposal in Cairo

A study launched in Cairo in 1995 has shown that wastewater treatment can address not only the Egyptian city’s water pollution problems but also open new opportunities for business and agriculture. The Greater Cairo Wastewater Project will produce about 0.4 million tonnes of sludge or biosolids annually from wastewater treatment.The study was initiated under the Mediterranean Environmental Technical Assistance Programme funded by the European Investment Bank and promoted by the Cairo Wastewater Organization. Initial results show that sludge can be effective in growing wheat, berseem clover, forage maize and grape vines. Digested sludge offers significant nitrogen fertilizer replacement value to farmers; no harmful effects of biosolids on crops were detected in field trials; and the benefits of spreading biosolids on newly reclaimed soils are expected to increase with cumulative applications. Farmers in Egypt are prepared to pay for bio-solids due to the scarcity of manure and the high costs of inorganic fertilizers.

Source: UNCSD 1999